The Internationaler Sozialistischer Kampfbund, usually shortened to ISK, emerged in the mid‑1920s as a small but remarkably disciplined socialist cadre group centred on the Göttingen philosopher Leonard Nelson and his circle. It broke away from the broader workers’ parties of the Weimarer Republik and aimed to educate and train future leaders for a new, ethically grounded socialist society rather than chase mass membership. Politically, the ISK rejected both Marxist orthodoxy and clerical influence, placing a strong emphasis on individual responsibility and moral steadfastness, which gave its members a very distinct profile in the crowded left‑wing milieu of the time. Göttingen played a key role in this, because the university and Nelson’s teaching there served as a magnet for young people willing to combine philosophy, pedagogy and political engagement. From this provincial academic town, ideas were carried into wider networks of the labour movement across Germany.

When the Nazis rose to power, the ISK punched far above its weight in the resistance, despite numbering only a few hundred committed members. It engaged in illegal leaflet campaigns, maintained clandestine contacts with trade unionists and social democrats, and tried to push for a united workers’ front against National Socialism even after such cooperation had become dangerous. Members took part in acts of everyday sabotage and information work, such as distributing clandestine newspapers and helping persecuted comrades escape. Their insistence on personal discipline and secrecy allowed the organisation to keep functioning underground for longer than many larger groups, though arrests and exile eventually weakened it. After 1945 the group as such dissolved, and many former members flowed back into more traditional parties, especially the SPD, bringing their experience of resistance with them.

One of the things that stands out, especially when you know Göttingen a bit, is how far the ISK went in regulating everyday life for its members. Joining meant not just signing up for meetings and leaflets, but accepting a strict personal code: membership in trade unions and active work in the workers’ movement were expected, and income above a modest level was often handed over to the organisation. At the same time, there were far‑reaching lifestyle rules – members were required to live as vegetarians, abstain from alcohol and nicotine, and keep their distance from the churches, reflecting the ISK’s ethical socialism and antiklerical stance. Punctuality, orderliness and reliability were not just bourgeois virtues but markers of political seriousness, and sloppiness in private life was seen as undermining the credibility of their cause. In practice this produced a kind of tight‑knit community whose internal discipline made it more resilient when forced into illegality.

Leonard Nelson and Minna Specht

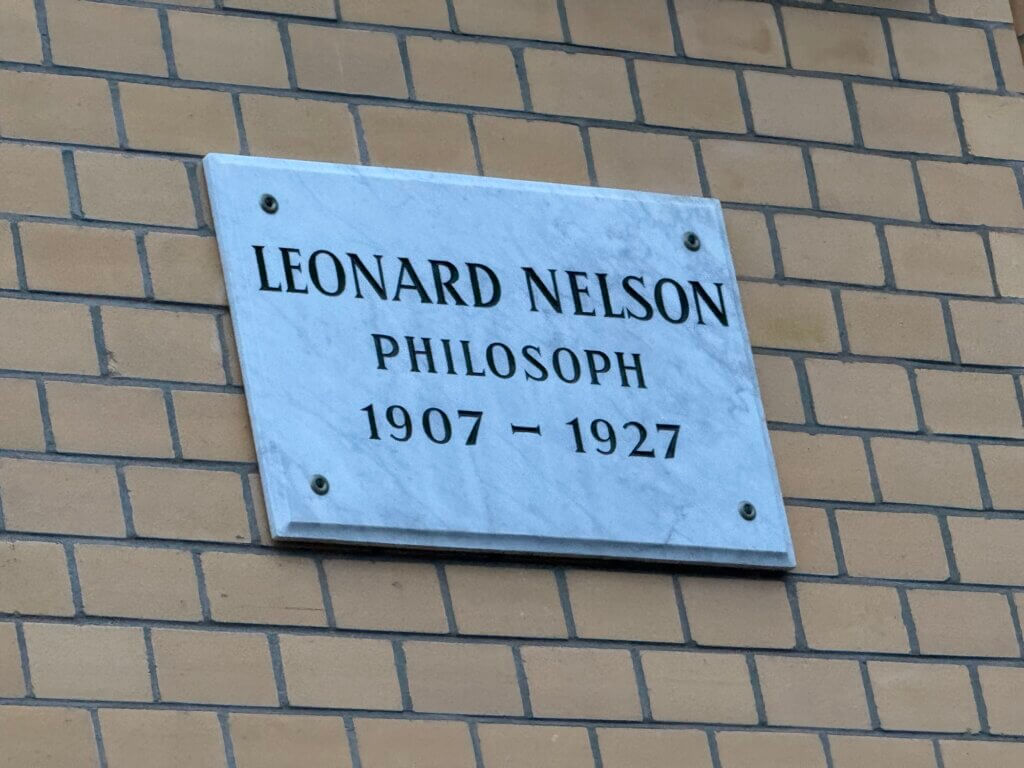

Leonard Nelson himself, a neo‑Kantian philosopher turned political activist, was the intellectual founder and early leader of this milieu. He had already launched the Internationaler Jugendbund in 1917 together with the educator Minna Specht, and from 1925 the ISK became the organisational expression of his ideas, combining philosophical seminars, political strategy and strict ethical demands. Specht, who had a background in progressive pedagogy, was not just his collaborator but a central organiser and later co‑leader of the ISK, especially after Nelson’s death in 1927. She ran schools inspired by the same principles of critical thinking, social responsibility and communal life, and during exile carried the educational and political traditions of the ISK into international contexts. Within the organisation, her role bridged theory and practice: she helped turn Nelson’s philosophical programme into concrete educational work and day‑to‑day organisation.

What is left today?

In Göttingen you can still trace these stories in the local streetscape if you know where to look. Nelson lived and worked for a time at Nikolausberger Weg 61, using the upper floors not only as private rooms but also as offices and guest accommodation for the circle around him, and the building there still stands today. A few metres further up the hill, at Nikolausberger Weg 67, once stood the ISK headquarters, sometimes referred to as the ‘rote Burg‘ (‘red castle’) which functioned as a hub for meetings, coordination and visitors. That house has since been demolished and replaced by a new building, so the physical traces of the ISK’s presence there have vanished, even if the address still marks an important point on the city’s political memory map. Walking that stretch of the Nikolausberger Weg, you move quite literally along the spine of a small but stubborn strand of German resistance history embedded in an otherwise quiet university neighbourhood.

A street close to the former location of the ISK has been named Leonard-Nelson-Straße and on the Zietenterrassen you can find the Minna-Specht-Eck and the Grete-Henry-Weg. Additonal streets remembering former ISK members are the Heinrich-Düker-Weg close to the main campus of the university and the Willi-Eichler-Straße in the industrial zone of the city quarter Grone.

Internationaler Sozialistischer Kampfbund (ISK)

Nikolausberger Weg 61 (former home of Leonard Nelson)

Nikolausberger Weg 67 (house of the ISK)

Göttingen

Germany

Loading map...