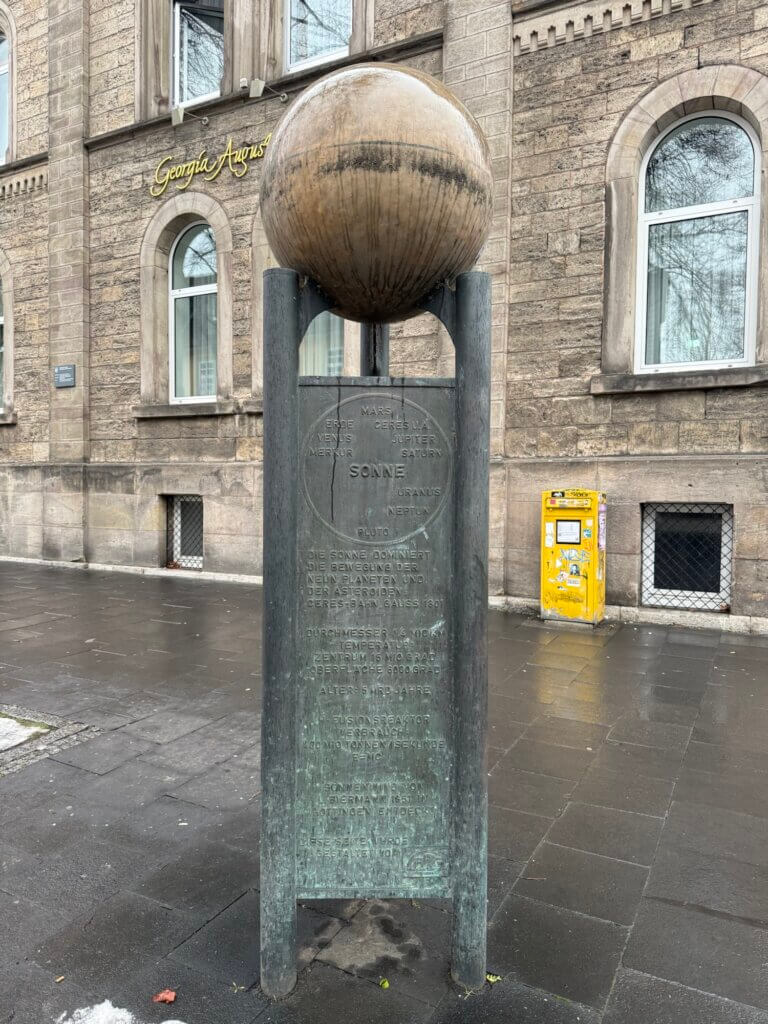

The Planetenweg in Göttingen is a fascinating blend of science, art, and landscape – a miniature model of our solar system mapped onto the real world. Stretching roughly 2.5 kilometres through the city centre to the outskirts, it’s built to a scale of one to two billion. That means every metre you walk represents about two million kilometres in space. The trail starts near the Göttingen railway station, where the Sun is depicted. From there, you can follow the path through the city up the hill, tracing the order of the planets as you move farther from the railway station.

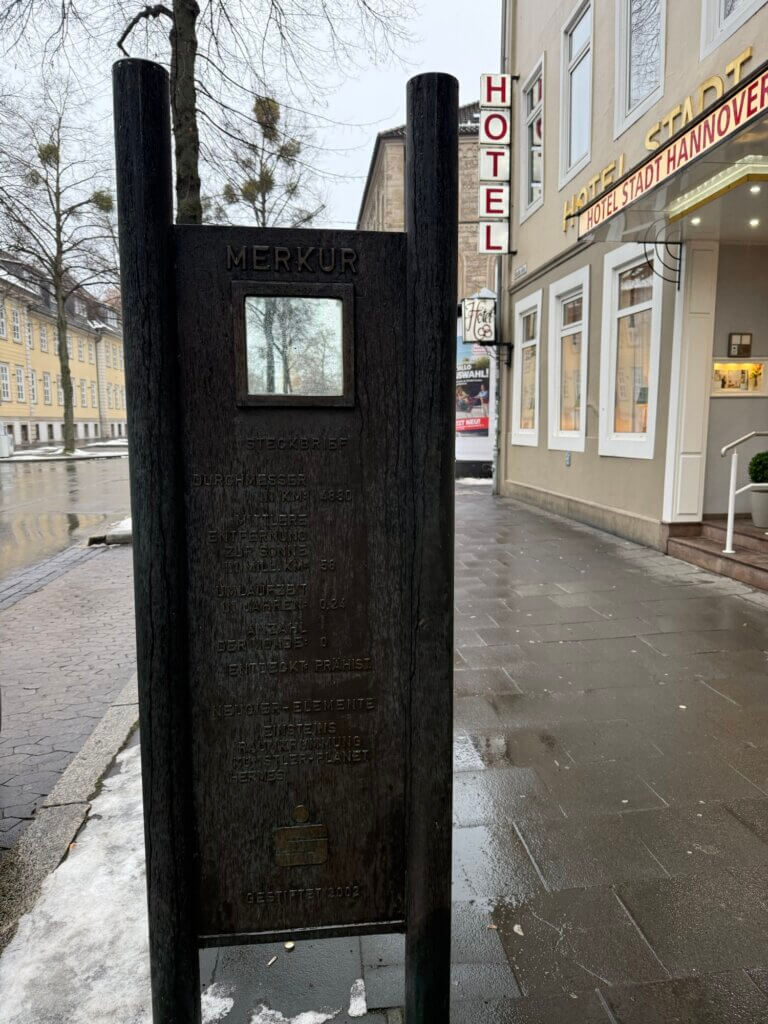

Each planet along the route is represented by a small sculpture or marker that provides information about its size, orbit, and position in the cosmos. Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars are encountered close together near the railway station – just as in reality they huddle around the Sun. Jupiter and Saturn lie further out. By the time you reach Uranus and Neptune, you’ve left much of the bustle behind; they sit quietly in the Ostviertel, reminding you how immense the distances between worlds truly are.

In recent years, the model has been updated to reflect changes in astronomical classification. Pluto, once the ninth planet, now has a new home in this Göttingen version of the solar system. It’s been relocated to the grounds of the Max-Planck-Institut for Solar System Research, which feels almost poetic – placing the ex-planet within the very institute that studies celestial phenomena in great depth. Visitors often note the symbolic fit: Pluto may have lost its planetary status, but its scientific and cultural significance endures within an institution devoted to exploring our universe.

Going even further, the Planetenweg doesn’t stop with Pluto. A remote station for Sedna, one of the distant trans-Neptunian objects, has been added near Diemarden, several kilometres beyond the official end of the main trail. It’s a clever way to convey the enormous scale of the outer solar system – vast, lonely, and stretching into the unknown. Reaching Sedna’s marker requires dedication, but for those who take the journey, it gives a humbling sense of just how small our familiar planetary neighbourhood truly is.

The planets

The eight planets of our solar system, in order from the Sun, are Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Each can be grouped as either a small rocky world or a giant gas or ice planet, and their sizes range from tiny Mercury to enormous Jupiter.

Mercury is the smallest planet, with a radius of about 2,440 kilometres, and it is a dense, grey, heavily cratered rocky body that looks similar to the Moon. Venus is only slightly smaller than Earth, with a radius of roughly 6,050 kilometres, and appears as a bright, creamy-white globe shrouded in thick clouds that hide its extremely hot surface. Earth has a radius of about 6,370 kilometres and stands out with its blue oceans, white cloud swirls and green-brown continents. Mars is smaller, with a radius near 3,390 kilometres, and is famous for its rusty-red colour caused by iron-rich dust, along with dark volcanic regions and bright polar caps.

Jupiter is the largest planet by far, with a radius of about 69,900 kilometres, and is a gas giant marked by alternating light and dark cloud bands and long-lived storms such as the Great Red Spot. Saturn, with a radius of about 58,200 kilometres, is another gas giant and appears pale yellow-beige, surrounded by its spectacular, bright ring system made of countless icy fragments. Uranus is an ice giant with a radius of about 25,400 kilometres, showing a smooth, subdued blue-green disc due to methane in its atmosphere. Neptune is slightly smaller, with a radius of about 24,600 kilometres, and presents a deeper blue colour, sometimes broken by dark storm spots and bright white clouds.

The outliers

Pluto is a dwarf planet orbiting in the Kuiper Belt, far beyond Neptune, on a long, stretched-out path around the Sun that takes about 248 Earth years to complete. It is relatively small, roughly two-thirds the diameter of Earth’s Moon, with a diameter of about 2,370 kilometres and a mixture of rock and various ices making up its interior. Its surface is surprisingly varied for such a distant world, with bright nitrogen-ice plains, darker, reddish-brown regions, rugged water-ice mountains and many impact craters. In colour images it appears mostly pale brown to reddish, with lighter patches such as the heart‑shaped region informally known as Tombaugh Regio giving it a mottled, patchwork appearance.

Sedna is a distant trans‑Neptunian object on an extremely elongated orbit that carries it far into the outer reaches of the solar system, well beyond the Kuiper Belt. It is smaller than Pluto, with an estimated diameter of about 1,000 kilometres, placing it between typical large asteroids and the larger recognised dwarf planets. Sedna is thought to be composed mainly of rock and ice, with a surface coated in frozen substances such as methane and nitrogen that may have been altered by radiation over immense timescales. Observationally it appears as a faint, reddish object, its colour probably the result of complex organic molecules (tholins) forming on its icy surface under constant bombardment from cosmic rays and ultraviolet light.

Planetenweg

Göttingen

Germany

Loading map...